Our Chiefs And Elders

Our Chiefs and Elders

Published: 1992

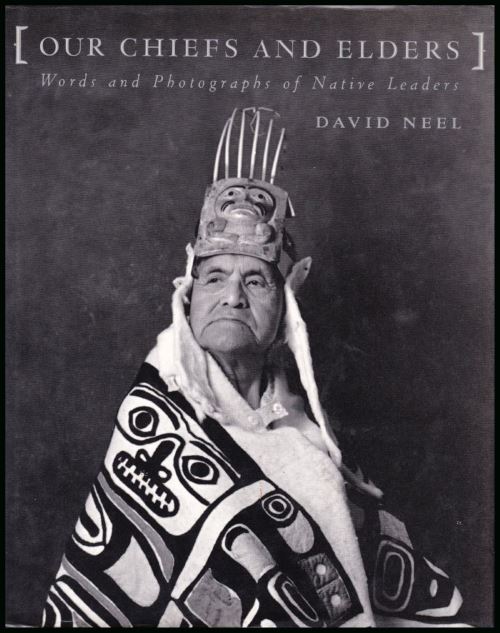

When I set out to photograph the Native leaders of British Columbia, I was not aware of the effect the experience would have on my life Four years and three babies later, a book is born. This body of work is intended to be the antithesis of the 'vanishing race' photographs of Native people this is a statement of the surviving race. It has been my intention to let the people speak for themselves. For this reason the text appears as unedited as possible, as it was told to me between 1988 and 1991. These people serve as the conduits of a knowledge that has come down through time to be handed on into the future. Through their words, it is my hope that you will be able to see beyond the stereotype to the person behind and gain a better understanding of what Aboriginal culture and people are about. History has shown that allowing people to tell their own story is the only way a greater understanding between cultures can occur. The photographs are my interpretation, my vision, of these human beings. I photograph these people as I do all races, striving to go behind the physical appearance to show the humanness of, or common thread between, people.

This, it seems to me, is of particular importance at this tame, as the Native and non-Native nations work toward setting aside the errors of the past to define a new relationship. It seems fitting that the words of our leaders should add to the process of understanding at this time, the quincentennial of the discovery of Christopher Columbus by Native Americans. It seems so basic, in searching for knowledge about a people, to talk to the leadership. The elders tell us that we need to know the past to understand our present and future. The time has come for the First Nations to speak for ourselves and to create our own images. And who knows better than our leaders what those images are?

My photography has been influenced by the 'concerned photographers,' such as Cartier Bresson, Cornell Capa, and W. Eugene Smith. These are men idealistic enough to believe that photographs can make a difference - that they can help humanity understand itself. I would like to believe this myself, but what I feel is hope rather than belief. Certainly photographs greatly influence our understanding of the world, so it is important that there are photographers working to illustrate what they see as the truth. Perhaps my biggest influence has been W. Eugene Smith, the Life magazine photographer and father of the photo-essay. He told the Story Of many people, including that of the people of Minamata, Japan, and their struggle with industrially induced mercury poisoning. Unfortunately, like many great artists, he died poor, with a great talent and an incredible body of work. I greatly admire people, like Smith, who stand for what they believe through times of trial. An artist or photographer needs that strength of vision to see him or her through the difficult periods. Another major influence on my work was provided by Irving Penn, an artist and commercial photographer whose technique is brilliant. His 'Worlds in a Small Room' approach has an obvious influence on my work, although I take a 180 turn from him with respect to how I approach my subject. His images are impersonal, crafted for immediate Impact, and illuminate the strangeness of the sitter. This is the approach of much of the magazine photography we see today. l, on the other hand, strive to photograph that which is common between us, though a person may look and dress quite differently from you or l.

As I set out to photograph the chiefs and elders, I thought that I would be seeking out the oldest and the wisest. As I met people, it became clear that each had a contribution to make. Like chapters in a book, they come together to tell a story. Research and selection was carried out through word of mouth - what anthropologists used to call 'informants' and 'fieldwork.' By talking to people I would be led from one person to the next. When I planned to visit an area I would talk to one or two acquaintances from that village or tribe and get a name or two. I invariably found my way to someone who became a 'chapter' in this book. I feel that the selection of people included in this collection constitutes a reasonable representation of Northwest Coast elders - at least Insofar as any group of fifty or so people could. In hindsight, it seems as though was being led to the people I needed to meet with. Like the process of photography, this seems extraordinary.

When I photograph people I set up my equipment, we talk, I take pictures, and it is a relaxed, shared experience. When the photographs are developed, and one selected, a visual statement about that person and their life is the result. I have never understood the process at an intellectual level - it is more a matter of intuition - and I've simply come to trust it. Photography, at its best, can go behind the physical self to reflect a person's soul on a piece of sensitized paper. When it works, it is magical - and the longer I take pictures the more often the magic works. I approach photography as a personal vision. What the pictures say, to some degree, embodies what I choose to say about the person and what I feel about him or her. Photographs are not objective. Once this is recognized, one can see a portrait for what it is - a result of an interaction between two people. A photo session is a sharing experience - I try to share with my subjects, as they share with me, the resulting Image. I have made an effort to have these images project truthful representations of the leaders. I am aware that photographs live on beyond the subjects or photographer, and it is my hope that these will be found to be fair representations as time moves on and they become a part of history.

In an effort to show the people in their fullness, as individuals, I have photographed them in a variety of activities and settings. Native people are and do many things. Everything shown is real - a part of their lives. The ceremonial regalia, depicting crests and lineages, are owned and used by the subjects. I have tried to show the people as they are, with their lives in two worlds, two cultures. While they may live in modern homes, drive automobiles, and attend rallies in the city, they tenaciously hang on to their traditional ways and values. Whether you fish in a canoe or a gas boat, or carve totem poles with metal or stone tools, is not the issue. Indigenous people have a place in contemporary society, and their traditional culture has come with them. These photographs strive to illustrate this.

I learned much while talking to the chiefs and elders. In part it was a process of self-discovery and education. I was born into a family with a long history in Kwagiutl art. My father and grandmother, both artists, I lost in my childhood and so was raised by my mother in Alberta, away from my father's culture and people. During this time, my mother taught me to stand on my own feet - to be self-sufficient. Later, my elders spoke to me of the importance of self-sufficiency. After living and travelling in Canada, the United States, and Mexico, I returned home, an adult and a photographer, to see the Coast with new eyes. Upon my return, I was intensely curious about my culture and heritage and sought to continue the social/documentary photography, in addition to the commercial work, I had been doing in the United States. It was two years before I had a vision of what I felt I wanted to do. It seemed obvious that the elders and chiefs were the foundation, and I began to seek them out. This project, undertaken in my late twenties, was to be my education, my 'master's degree,' in my culture. As is the case with learning, what I learned was how much there is to know, and how little of it I know. It made me long for the time of my grandparents, when extended families were close (four to six families sharing a bighouse) and were headed by an elder or elders who daily passed on age-old knowledge. As we learn from our elders, we find it's not necessary to reinvent the wheel in our youth. Inherited knowledge allows us to learn from the mistakes of previous generations.

I came to mourn what had been lost as well as to take joy in how much remained. The elders of this generation will be the last to witness the time before cars and gas boats. Many were born in bighouses, traveled in log canoes, lived from the land, and some still speak only their own Native language. We will not see elders like this again, I am afraid. The roles of elders, hereditary chiefs, elected chief councilors, and youth became known to me. The people shared much with me because I was a young person who wanted to know. This is what is called tradition - the passing on of knowledge to the young who want to know. I came to understand that lifestyle will always change - what is important is that the culture, language, and values be retained. This takes a real effort on the part of the people. Today we are witnessing the rebirth of our cultures on the Northwest Coast. We can see the end of a period of oppression, and we can see a time of hope for our grandchildren. We are entering into a time in which Aboriginal people have a place in contemporary society. The Native has learned much it is now time that society learn from the Native.

My desire to photograph the leaders began as I slowly came to realize that, for well over a hundred years, we have learned to accept a false image of the people of the First Nations. The tool used to build this image has been the camera, and the subject has been the 'Native Indian.' This image has not been a kind one, and it has laid the foundation for a century of misunderstanding between Natives and non-Natives. For this reason, the First Nations are realizing the need, and acquiring the skill, to represent ourselves to the world. We live in a time of the created image - if you do not create your own, someone will create it for you. The image created for us is one of a people stuck in time, as though we are not part of the twentieth century. As early as the mid-1800s, Native people were viewed as part of the past and were imagined to be a 'vanishing race.' Cultural evolution is not something in which we are seen to participate. Our history ended with the coming of photography and Hollywood. I have heard people ask many times, 'Are there still Indians today?' When depicted in popular culture, we are ether a 'noble savage' or a 'degraded heathen. Both are one-dimensional stereotypes, which flatten human individuals into created, dehumanized classifications. This treatment is not limited to Native people - just look at your evening newspaper or TV news. But who else has been painted so generally with so broad a stroke? Not that the early photographers, anthropologists, and ethnologists had universally bad intentions. Ethnocentricity and a feeling of cultural superiority were the standard of the day. This colonial mentality colors the image-making of Native people even to this day.

The process of misinformation and colonization was aided by both the arts, such as photography, and by the sciences, such as anthropology. Many of the sciences have been applied toward proving the inferiority of the First Nations. Social Darwinism has been taken to prove that the colonizing nation, or more 'highly evolved' race, has a right to do what it pleases with the First Nations, and that this simply demonstrates the 'survival Of the fittest.' The First Nations, according to this position, are, by definition, inferior. Thus human society and relations are reduced to the level of an ant colony. An essential measure of the 'progress' of a society may be defined by how seriously it critiques the colonialist roots by which it obtained its 'original' territory. Colonialism, by nature, sets aside the rights and history of one people for the needs and desires of another - always with disastrous effects.

Photography has been used since the last century to support these ideas of cultural superiority, to the loss Of the First Nations of the world. The roots of this ethnocentric attitude began before the popular use of photography. When the tall ships first began to visit North America, artists were present to record and interpret the 'discovered' people. Artists were to produce the first images of Native life and culture for a White audience. The filtered image began its life here - with broad artistic license being applied. It was typical for tribal groups, settings, and cultural practices and items to be moved back and forth in order to produce a finished painting. This practice laid the foundation for the approach to contemporary photography in which the desired image is molded by adding props, deleting signs of contemporary life, and selecting background to correspond to White ideas of the 'authentic' Native person. The goal was not to Strive for a fair or accurate depiction but for visual impact, or viewer response, to the image. The manipulated image became the accepted norm, as it continues to be today. The thirst for manipulated photographs, and the diversion from truth, was augmented with the rise in popularity of collecting photographs of 'noble savages.' This market for photographs of 'savages' as curiosities was such that, by the 1880s, a high degree of control in the portrayal of Native subjects was the accepted norm. Today it is still a popular pastime to collect 'Indian photographs, some of which fetch prices in the thousands.

Most Native photography occurred during a painful period of Native American history. A good deal of omission, selection, and propping was required to mold a publicly acceptable image. There was a market for photographs of the noble savage, not the degraded heathen. Since Native people were, at this time, combining Western clothes, tools, and so on with their own culture, some careful filtering was required to show the 'savage' in his or her most 'primitive' state, as the market dictated. Although the noble Savage was the dominant image of the day, there were photographers interested in showing the Story of contact and change. Of these the most notable are perhaps Lloyd Winter and Percy Pond of Juneau, Alaska. Although there was a minority of photographers creating truthful images, the romanticized noble savage was the mainstay of the day.

There were many photographers of this genre, but it was Edward S. Curtis who most influenced North American attitudes about Natives. Probably the most well-known and prolific of the so-called 'Indian photographers,' Curtis was to take the romantic savage myth one Step further into the 'vanishing race' myth. The premise of his work was that North American Natives were a 'vanishing race,' and it was to be his life's work to 'save' them from this abrupt end by capturing them on film. This grand enterprise was undertaken with the endorsement of Theodore Roosevelt and with the $75,000 financial backing of J. Pierpont Morgan. A newspaper headline of the day read, 'Morgan Money to Keep Indians from Oblivion.' The result was The North American Indian, a twenty-volume set of photographs and text, which has done more to misinform and shape attitudes toward Native people than the work of any other photographer. When Curtis's photographs are viewed as art, they are quite wonderful. However, they are very problematic when one starts to examine them for authenticity, integrity, and general content.

The main problem Curtis's images create has to do with the idea of the vanishing race. There was a commonly held belief that the Native people of North America were vanishing and would soon be gone. This was desirable for the time, as the territory they historically occupied was wanted for Caucasian immigration and expansion. Curtis's vanishing race vision became popular following the Indian Wars in the United States. It coincided, approximately, with the potlatch and Sundance prohibition era in Canada and the United States and with the flu and smallpox epidemics in various communities. There was active suppression of Native culture and oppression of the people - at a time when there was a public desire for images of 'authentic' pre-contact Natives in their primitive State. At the same time that the culture and people were being systematically uprooted, there was a need for images affirming primitive humanity in touch with the natural world. This was also an era of technological and industrial boom and belief in unlimited growth potential. It was as though the public wanted confirmation of the existence of a frontier - an image of a primitive human, existing like a hunting trophy or a fish in an aquarium.

From this foundation Curtis set out to capture the Native as he/she existed many years previously. This required some effort and ingenuity, as he got started in approximately 1900, and his vision of the 'primitive' Indian was from 100 to 200 years in the past. He steps outside time to accomplish this, thereby misleading his audience, who thought (and continue to think) that they were seeing how actual, individual people really lived at that time. A very fine photographer, he was nonetheless able to manipulate his images without the encumbrance of professional ethics or conscience. In his quest for his personal vision of authenticity, and to fit the publicly accepted notion of the 'primitive Indian,' he often supplied his subjects with wigs and props. His views of the romantic savage were typical of the times. In addition to using wigs, he has been criticized for dressing subjects in clothing that actually belonged to other tribal groups. This visual cocktail is comparable to photographing a French woman in a traditional Italian dress and offering this as an image of an 'authentic' European. Curtis, as knowledgeable as he was of the vast differences between tribal groups, and even villages, felt free to mix and match as desired. This 'pan-Indian' approach has continued to be the standard for dealing with Native people in popular culture (e.g., Hollywood).

Curtis's tactics for making his photographs did not stop short of lies, bribery, and deception. His unethical and compromising attitude toward his Native subjects is seen in his 'Sacred Mandan Turtles' photograph. In order to photograph these sacred ritual objects against the wishes of the Mandan people, he bribed a Mandan priest, Packs Wolf. After many months of effort, Packs Wolf 'consented' and told Curtis to come in early winter. Following partaking of a sweatlodge to 'purify' himself, he was able to photograph the sacred objects. However, he was nearly caught and had to pretend to be recording the priest singing in order to cover his actions. Practices of this sort were not unique to Curtis - deception of Native people was common. Even the renowned anthropologist, Franz Boas, was known to use bribery to obtain ritual items against the traditions and wishes of the people. He was also known to rob graves by night, which was a common feature of the anthropology of the day. Today, the remains of thousands of Native people are stored in the archives of the most 'credible' museums and institutions, and this has become a contentious issue, as descendants are rightfully demanding the return of their ancestors' bones. This disrespect was pervasive in the collection of material dealing with Native people. Such actions as grave-robbing were acceptable because anthropology, and other studies associated with Native people, was based on the idea that they were inferior and not deserving of the basic human rights due the Caucasian race. Photography has been used, with a good dose of manipulation, to support this attitude.

It has laid the foundation for the way non-Natives have thought, and continue to think, about Natives. The work Of Curtis is good art. His skill in portraying his subjects is timeless - a testament to his abilities as a photographer as well as to his rapport with Native people. Today, there continues to be a lucrative market for photogravures of his photography. However, their popularity with collectors and as illustrations of Native life continues his campaign of misinformation. The vanished race myth lives on. It is unfortunate that Curtis did not at least choose to show the contemporary living conditions of his subjects, in addition to his own misguided vision.

The impact of the 'Indian Photographers' has been large. They have become the visual norm in the popular misunderstanding and depiction of Native people. Today, these photographs are seen on calendars, postcards, and in numerous books. The photographs have become disassociated from their context and are accepted as genuine. They continue to support the vanishing race attitude toward Aboriginal people, perhaps more than ever because of increased circulation and acceptance. What is most disturbing is that these images have come back into our communities to influence how our own people look at our culture and heritage! Due to a lack of understanding, our young people interpret these photographs as accurate depictions of our ancestors and their way of life. The very sources of public education, our Native cultural centers as well as public museums, distribute this material as authentic ethnography, when they are, at best, loosely based re-creations. The public image of Native people has not been widely modernized since the last century hence, Native Americans have become vestiges of the past. This attitude has been transplanted to other parts of the globe as well, where it supports similar expansion and resource exploitation. The reality of contemporary Native people and their culture is only now starting to trickle out.

The public has had little opportunity to see why issues like self-government, the land question, and fishing and hunting rights should be connected with a 'vanishing race.' On a recent research trip to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, I heard a museum guide talk about a 'potlatch that was' and 'Indian people that were.' I thought of all the potlatches I have attended in recent years and of all the 'Indians' I know - many of them relatives. What has vanished is the lifestyle - the people remain. We remain as people, as nations, striving to hang on to the valuable parts of a culture handed on to us through our elders. Native people are not vestiges of the past, as much photography leads us to believe. First Nations evolve, as every culture of the world evolves. When a culture stops moving, and ennui sets in, so does decadence. Native people have been depicted as part of another age because White governments have deemed it convenient to do so. To recognize Native nations would mean recognizing human rights, self-government, and the land question. To acknowledge First Nations would not be consistent with the ban against potlatches between 1884 and 1951, Wounded Knee (1891), or the Gitksan/Wet'suet'en decision (1991). This dichotomy has served White society well. As we of the First Nations are learning to speak for ourselves, it is becoming increasingly difficult to believe in the images of the past.

We are learning to use the tools of contemporary society, in some cases the very tools that have been used against us. Until the middle of this century, we did not have a right to hire lawyers, raise for the pursuit of legal cases, or even to exercise the federal vote. Today, these and other tools are being used to improve our lives. During the constitutional amendments of the 1970s, the Native people of Canada had little direct political redress when their concerns were overlooked. In the constitutional accord of the 1990s, we were to see an elected Native MP stop the Meech Lake Accord, when, once again, we were left out. In British Columbia, we are witnessing negotiations and modern-day treaties being undertaken by tribal, federal, and provincial governments. The courts have become the arena for settling long-standing issues such as the land question. Some of these cases are multi-million dollar affairs, encompassing years of research and extensive legal teams. The 52.5 million Gitksan/Wet'suet'en land claim action, which ended in 1990 after three years of trial, is an example. It is also a testament to the enduring attitudes of cultural superiority held by people of power within the Canadian

Infrastructure. Chief Justice Alan McEachern, in his Reasons for Judgement, states his belief that 'aboriginal life in the territory was, at best, nasty, brutish, and short.' He also suggests that, prior to White occupation, 'the Indians of the territory were, by historical standards, a primitive people.' Other legal actions have resulted in more balanced for example, the Sparrow decision decisions regarding Aboriginal fishing rights.

The communication arts are being employed to tell the First Nations viewpoint. Artists, writers, filmmakers, and performers are using modern media in addition to their traditional cultural ways. This book is part of that trend. What has historically been a non-written or orally transmitted culture has come to utilize many media. The result has been access to a much larger and more varied audience.

The First Nations of British Columbia are ancient and have always had something to Share. The sharing was once more equitable - until smallpox and flu epidemics resulted in great population loss. Among my people, the Kwagiutl, the population went from 10,700 people in 1835 to 1,854 people in 1929. The tribes had well-defined territories, and these were respected. Originally, there was much trade between Natives and non-Natives. The First Nations have shared much with their new neighbors. What the Native culture has to share today is not technology but a knowledge, spirituality, and approach to living with our earth that are thousands of years old. Much modern medicine has been derived from ancient Aboriginal methods. It is only after we peel away the layers of ethnocentrism and lay aside feelings of cultural superiority that we can hear what the chiefs and elders have to tell us.

It is becoming apparent that technology and development are only part of the equation. Economics has become the main ethic of Western society. This system of 'scientific materialism' means that nothing matters unless it can be measured or quantified. Humane and environmental values and Obligations are left out of this equation - a world-view that is short-sighted and fatally flawed. For example, when a country adds up its gross national product, it fails to make a subtraction on the other side of the ledger to account for the lost timber, forests, and such related environmental destruction as the decimation of fish-spawning habitats. These losses represent an actual reduction in 'Inventory' and reduce Income and job prospects for the future. This omission is especially significant with respect to deforestation, In which case, because the resource cannot reasonably be expected to regenerate, the environment suffers a permanent loss. Any business that used this kind of accounting method would not be around long. The chiefs and elders have a different world-view to share.

Included in each leader's text is certain factual information: English name, date of birth, tribe or nation, present home, and parent's names. Their Native names were also recorded but were not included because of the difficulties in correctly transcribing names belonging to many distinct languages. The name and date of birth help place them in history - today or 100 years from now. These are people from living cultures, and their age and the period they were born into are significant when you consider the stories they have to tell. Their tribe is designated as indicated by the person, not by linguistic grouping, as is the anthropological norm in the portrayal Of Native people. For example, what is often referred to as 'Coast Salish' refers to what today consists of over fifty tribes from Saanich, Nanaimo, Halalt, and so on. Names of parents are important in understanding 'who you are and where you come from.' Heritage and extended family are the foundation of Native peoples' world-view and identity. When an elder asks, 'Who are you?' he or she is asking, 'Who do you descend from? What are your roots?' For Native people it is a source of pride, as well as essential, to be able to recount their respective lineages up to five generations or more. This is also practical for doing research on the potlatch, chieftainship, or even in more academic areas (e.g., marriage between tribes, migration of culture).

First Nations leaders consist of elders, hereditary chiefs, and elected chief councilors. The elected chief and council form of band government was Initiated by the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) in Canada, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the United States, in the early twentieth century. A number of tribes, or nations, have developed various forms and levels of self-government as an alternative to this system. Under the DIA different peoples have been divided by language into tribes or bands. A tribe typically refers to people from a given village site or area, although the northern peoples use this term to refer to clan systems (e.g., eagle clan or tribe). These bands or tribes are organized into tribal councils or nations with specific historical or cultural affiliations (e.g., Kwakiutl District Council, Nuu-Chal-Nulth Tribal Council). The tribal councils exercise varying degrees of self-government and autonomy over their affairs. It is important to remember that there is this variation from area to area, and that, in some cases, certain designations are English words for Native concepts.

Historically, tribal government was based on a system of hereditary chiefs. There was a head chief for a given tribe and a number of sub-chiefs. These chiefs held 'seats' which carried 'names' and were constant throughout history; only the Individual holding the position changed. Such chiefs had certain responsibilities to perform (e.g., potlatching) as well as responsibilities for territory, rivers, and so on. The system was undermined through the law on the potlatch, DIA policy, and funding arrangements. It is still in place, with varying degrees of application, throughout the Northwest Coast. In some areas, hereditary chiefs are in administrative positions, and in others, they play a more 'cultural' role.

The roles of elders are still very much alive, though they too have been reduced because of the residential school system. Until the 1970s, school-age children were made to attend boarding-schools, often far from home, for all their schooling. In addition to teaching reading and writing in English, the schools attempted to eliminate Native languages and values - strict punishment being the norm for speaking your language, practicing your culture, or eating traditional foods. It is now being disclosed that physical and sexual abuse perpetrated by the people charged with the care of these children was rampant across Canada. This has resulted in criminal charges, jail terms, the apology and resignation of an archbishop, and formal apologies by culpable churches, but such abuse continues to be an open wound in our communities, with the people and their descendants continuing to suffer from shame and other debilitating effects. The residential schools continued for enough generations to seriously disrupt the family System. Today, the role and knowledge of elders are being preserved and respected to the best ability of the people. The roles of elders vary from area to area and from family to family. Throughout the Coast area they are recognized as a great resource. Elders often play a role in the political process as well as in the general culture. It is their inherited knowledge, as well as their perspective (derived from experience), which is valued. In the Native way, memory or history is a tribal or family responsibility and is held and passed on by the elders.

In this book, the chiefs and elders share some of their knowledge about respect. Respect is the foundation for all relationships: between individuals, with future and past generations, with the Earth, with animals, with our Creator (use what name you will), and with ourselves. Respect is both simple and difficult, small and vast. To understand it and apply it to our lives is an ongoing process. This is the most valuable lesson the leaders have for us. It is not a lesson that can be explained with the simple formula, 'Respect is ...' For the Kwagiutl, the potlatch is a ceremony which allows us to show our respect in a public setting. We show our respect for the chiefs, the elders, those who have passed, those who have just come, for couples who are joining their fives and families, and so much more. Our potlatch is in a period of rebirth and growth, following the end of restrictions on the potlatch in 1951. The world is growing smaller, and, increasingly, there is the need to respect and understand our neighbors. Our Earth also requires respect. Respect yourself and you will respect others, I am told. The chiefs and elders have shared much with me. In reading their words, and looking at their faces, I hope you will feel they have something to share with you.