Kwakiutl People

The Kwakwaka'wakw peoples are traditional inhabitants of the coastal areas of northeastern Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia. Originally made up of about 28 communities speaking dialects of Kwak'wala, some groups died out or joined others, cutting the number of communities approximately in half. After sustained contact beginning in the late 18th century, Europeans applied the name of one band, the Kwakiutl, to the whole group, a tradition that persists. The name Kwakwaka'wakw means those who speak Kwak'wala, which itself includes five dialects.

Language and Culture

A member of the Wakashan language family, Kwak'wala is related to other British Columbia Aboriginal languages like Nuu-Chah-Nulth (Nootka), Heiltsuk (Bella Bella), Oowekyala and Haisla (Kitamaat).

The culture of the Kwakwaka'wakw is similar to that of their northern neighbours, the Heiltsuk and Oowekyala peoples. In addition, trails across Vancouver Island made trade possible with Nootka villages on the west coast of the island. Archaeological evidence shows habitation in the Kwak'wala-speaking area for at least 8,000 years. Before contact with Europeans, Kwakwaka'wakw fished, hunted and gathered according to the seasons, securing an abundance of preservable food. Consequently, this allowed them to return to their winter villages for several months of intensive ceremonial and artistic activity.

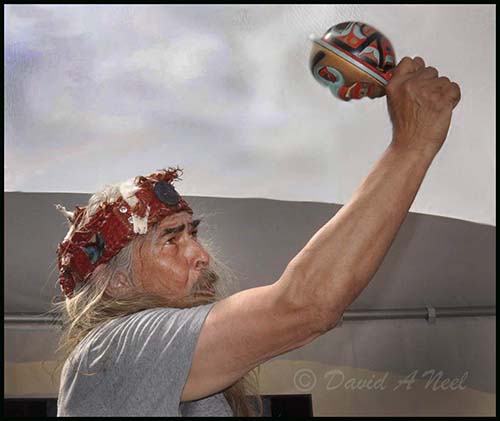

The Potlatch

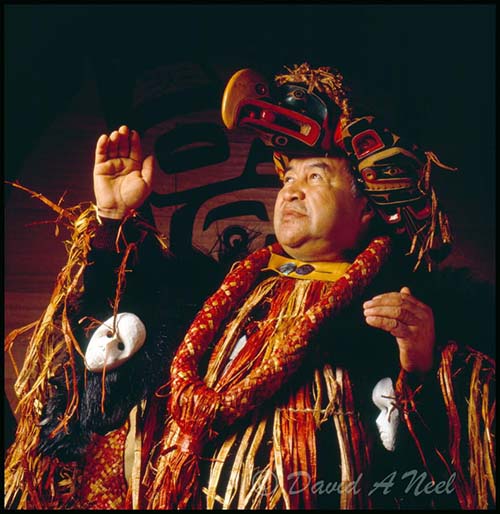

The potlatch, a ceremonial distribution of property and gifts unique to Northwest Coast peoples, was elaborately developed by the southern Kwakiutl. Their potlatches were often combined with performances by dancing societies, each society having a series of dances that dramatized ancestral interactions with supernatural beings. Those beings were portrayed as giving gifts of ceremonial prerogatives such as songs, dances, and names, which became hereditary property.

In 1885, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the potlatch and making it illegal to practise.

O'wax-a-laga-lis, Chief of the Kwagu'l 'Fort Rupert Tribes', said to anthropologist Franz Boas on October 7, 1886, when he arrived to study their culture:

We want to know whether you have come to stop our dances and feasts, as the missionaries and agents who live among our neighbors [sic] try to do. We do not want to have anyone here who will interfere with our customs. We were told that a man-of-war would come if we should continue to do as our grandfathers and great-grandfathers have done. But we do not mind such words. Is this the white man's land? We are told it is the Queen's land, but no! It is mine.

Where was the Queen when our God gave this land to my grandfather and told him, 'This will be thine'? My father owned the land and was a mighty Chief; now it is mine. And when your man-of-war comes, let him destroy our houses. Do you see yon trees? Do you see yon woods? We shall cut them down and build new houses and live as our fathers did.

We will dance when our laws command us to dance, and we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, 'Do as the Indian does'? It is a strict law that bids us dance. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you come to forbid us dance, be gone. If not, you will be welcome to us.

Eventually the Act was amended, expanded to prohibit guests from participating in the potlatch ceremony. The Kwakwaka'wakw were too numerous to police, and the government could not enforce the law. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offence from criminal to summary, which meant 'the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence'

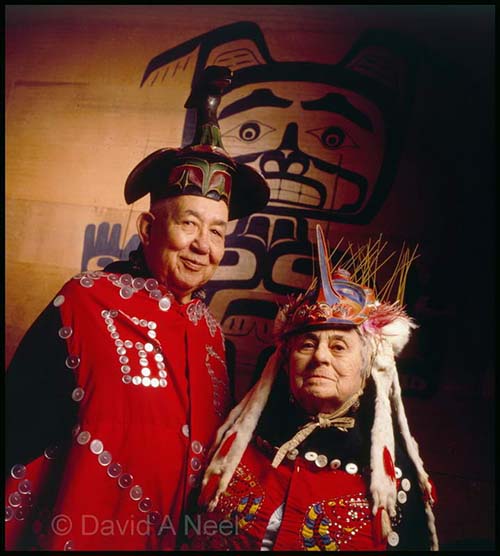

Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, in the 21st century the Kwakwaka'wakw openly hold potlatches to commit to the revival of their ancestors' ways. The frequency of potlatches has increased as occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright.

Contact with Europeans

In 1792 Spanish explorers Dionisio Alcalá-Galiano and Cayetano Valdés, and British Captain George Vancouver encountered most of the south Kwakwaka'wakw groups. Farther north, in 1849 the Hudson's Bay Company established Fort Rupert, which operated until about 1877, when it was sold to Robert Hunt, the fort's last factor (trader). George Hunt, Robert's son, worked with anthropologist Franz Boas, and together they recorded a large body of material on the language and culture of the Kwakwaka'wakw.

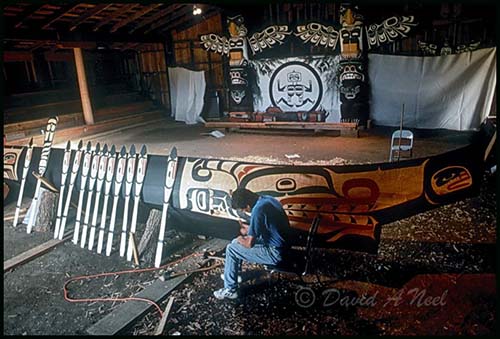

In 1884, a federal law prohibiting the potlatch threatened to destroy Kwakwaka'wakw culture. In 1921 a large potlatch at Village Island resulted in the arrest of 45 people. Twenty-two were imprisoned; their ceremonial goods confiscated. Knowing these masks and other ritual objects had been wrongfully taken, the Kwakwaka'wakw in 1967 initiated efforts to secure their return. The National Museums of Canada agreed to return that part of the collection held by the Canadian Museum of Civilization, on the condition that two museums be built, the Kwakiutl Museum, now the Nuymbalees Cultural Centre, in Cape Mudge and the U'mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay

Kwakiutl People Today

The Kwixa and Kwakiutl negotiated an agreement with the Hudson Bay Company in 1850, which is known as the Douglas Treaty, that allotted them eight reserves. Most were located near Beaver Harbour; two more at the mouth of Keogh River and Cluxewe Rivers; and a larger timber reserve on Malcolm Island. Today the Kwakiutl First Nation has eight reserves on 295 hectares of land, and is pursuing a Land Claim. Kwakwak'awakw culture is active, and potlatches and feasts are held regularly. The village has a traditional Gukwdzi (big-house), and displays the Sisiutl (Sea Serpent) and Frog designs, which are common crests within the Kwakiutl Nation. The Kwakiutl / Kwakwak'awakw nation is prospering, and their traditonal Pacific Native culture is flourishing.